Before you read Chapter 3, here’s the end of Chapter 2: March: Primrose and Thorn for context.

M and I head into town, see a friend in the supermarket, trolley half-filled. G was widowed at Christmas when her husband, in his fifties, died of a heart attack while cycling to work. She looks lost and frail, all we can do is offer a hug and listen.

H cycled the fells with M for years, before life pulled them in different directions. H, with teenage children and school runs, gradually replaced weekend rides with family responsibilities. M, being older than most of his cycling friends, had watched this pattern repeat as riders of H’s age became fathers with less time for the fells and forests.

*

It is the early hours of the morning and we are lying in bed.

“You okay?”

“Just thinking about seeing G today. Still can’t believe H isn’t here.”

“I know,” I say. But the truth is, I don’t know what to say.

Chapter 3. April: Hello, Buttercup

Over a decade ago, I loved every moment cycling around Odense with my friend, Jette, felt safe. But I do not cycle here in England, don’t have the confidence, having fallen off twice into traffic.

As for mountain bikes, most of what M tells me about their engineering and technicalities goes over my head. But I know mountain bikes absorb the chaos under their wheels. Rocks, roots, sudden drops (as if the trail’s purpose isn’t the way through, but to throw the rider off.)

“Explain to me what 180mm of travel is again, exactly?”

“The distance the suspension moves to soften the impact. Gives the tyres grip and the rider half a chance of staying upright.”

I tap away on my keyboard while M tos and fros from the kitchen. He’s washed his bike, taken a shower, toasted bread. The familiar ritual of return from the fells, the mechanical aftermath of adventure.

“Where did you get to in the end?”

“Ambleside. Twenty-six miles, three-thousand three-hundred feet of climbing towards Hawkshead, via Claife Heights, to Iron Keld, Hodge Close Quarry, Tilberthwaite. Then down to the foot of Wrynose Pass, over towards the Langdales, through the valley to Loughrigg Terrace and back to Ambleside. Two hours fifteen minutes.”

I note all of this down. ”How long would that have taken you on your old bike?”

“Three and a half to four hours.”

“About the same time it takes me to write a sentence.”

M appears in the doorway, ducking under the beam with practiced ease, and steps down into the dining room.

“Downsides... “ I say. M and I have been having this conversation for a few weeks now, because I can’t write this book without tales of his adventures on a mountain bike, so much a part of who he is. “Downside is the e-bike takes a bit of your fitness away, right?”

“Yes,” he says. “Some people don’t bother going out for a month. Battery anxiety is an issue as well.”

“Battery anxiety? It’s another language.”

M’s bikes have evolved through the years, each carrying stories of trails he’s ridden, friends he’s ridden with at different points in their lives. If you’re a cyclist or share your life with one, you could say that each bike serves as both object and archive, a physical repository of experience, falls, recoveries and the digital breadcrumb trails of routes tracked and logged through the GPS app, Strava. And for those of you who don’t cycle, or run, that app is the equivalent of a detailed diary that records every mile, every climb.

In April 2021, M turned sixty. We celebrated that milestone in the curious suspended reality of COVID’s third lockdown. Days earlier, shops had opened after months of closure. Outdoor gatherings remained restricted to a maximum of six. We still couldn’t socialise indoors with anyone outside our household. We couldn’t host the birthday celebration I’d imagined months before the pandemic. Instead, something intimate. There was M, me, our son and his girlfriend around our dining room table.

After our meal, we gathered around the computer to watch a short film. I’d been secretly collecting short videos from our family, our neighbours and M’s mountain biking friends, friends who’d shared hours of pedalling beside him, their rides now replaced by solitary outings during the deepest restrictions.

As familiar faces appeared one after another on the screen, each sharing a memory, a joke, a promise of trails to come, I watched the emotions move across M’s face. The film ended with an image of a premium e-bike.

“I didn’t have a clue as to what bike to choose,” I told him. “David Simpson was my guide, helped me no end.”

We look back at the screen, M’s face agog. “How?”

“Hire purchase,” I said. “Three years.”

Beyond the surprise of the new mountain bike, though, what the film truly represented was mutual support through rough terrain. Mountain biking had given these men, in their forties, fifties and sixties, a way to speak about vulnerability and resilience. Whenever M has shared their stories with me, I know I’ve been holding something not meant for casual retelling.

So now, as M approaches sixty-four and we prepare to leave Cumbria, I listen more closely to those conversations about bikes and trails, trying to absorb all the pleasure mountain biking has given him here over the years. And when we’re driving somewhere and M points out a trail he rode last week, or when he spends weekend hours servicing his bike, our talk inevitably turns to how e-bikes have extended riding careers.

“People with long-term injuries can ride power-assisted,” he says. “Also, as you get older and lose strength and power an e-bike assists you in those respects. More distance in a shorter time. It’s quicker.”

Beneath our chat lies an unspoken truth. The community built around these shared adventures will soon exist more in memory than in weekly experience. And while they didn’t see each other nearly often enough, H’s death makes this reality sharper, more immediate.

In January this year M and I had a flu-like virus. And now, as April unfolds, a lingering malaise settles between us. We aren’t fully sick or entirely well. I attempt lists of what needs doing, the tasks of preparing a house for strangers to judge worthy of their future. My enthusiasm for regenerating Bert’s garden last month has surpassed my body’s reserves. A gallbladder infection at the tail end of COVID lockdown, followed by an operation that inserted a stent through my bile duct, may have compromised my immune system.

Back then, a consultant suggested that village isolation, long hours alone with my thoughts, and the emotional weight of our son’s mental health might further compromise my body’s defences.

“Not the whole story,” he’d said, “but something we’re understanding more and more.”

A few years on, I understand better how stress works against my gut, killing off the bacteria that should’ve been protecting me. Of course, knowing this doesn’t stop the worry. M and I carry the weight of our son’s struggles with addiction. We lose sleep over his mental health. And, dear reader, I’ve got creaky suddenly. Of course, energy levels aren’t what they were at fifty, at forty. The body keeps its own accounts now, demanding payment for overexertion in ways it never did before. What used to be resilience feels more like borrowing against tomorrow’s reserves. Time feels different now, less expansive, more precious.

I look to the community archive to get over myself, coming back to the idea of a hedgerow game for the young parishioners in the village. A way that children might contribute to the community archive. The game could work as a progressive challenge that grows with each attempt. Rather than simply counting species, I imagine children could earn different badges based on their discoveries. They might start looking for five common species, say, blackthorn, hawthorn, dandelion, primrose, dog violet. Once they’ve mastered those, they advance to a tracker badge, looking for bird nests, insect holes in foliage, spider webs. The ultimate level might challenge children to look for evidence of ecological relationships.

Drafting a proposal to various community groups in the village, I consider what an adventure kit for children might look like. A kit parents could hire, for free, from the hall for a weekend family adventure in the village. A trail camera, entry-level binoculars, field recorder, bug box, bat detector, magnifying glass...

These activities are what I imagined M and I would do with our son when he was a toddler and beyond. We even named him after a woodland plant, dreaming of walks we’d take to meet his namesake.

But those early years went differently. Between my own struggles after birth trauma and the terrific strain that put on our marriage, M and I often chose the path of least resistance. Our emotional survival demanded more of our weekends than searching for our son’s woodland namesake did. The hedgerow game, the adventure kit, they’re a way of honouring what we lost and what might still be possible. I suppose I’m trying to acknowledge the grief of missed adventures while refusing to let grief end the story. There’s healing, isn’t there, in imagining children who will know the difference between hawthorn and blackthorn? Creating opportunities for other families feels like it’s part of what it means to leave well.

In any case, what are our collective responsibilities to the children who come after us? A trail camera and bug box, acts of resistance against a culture that separates children from the natural world. We can still cultivate attention, patience and wonder. One hedgerow at a time.

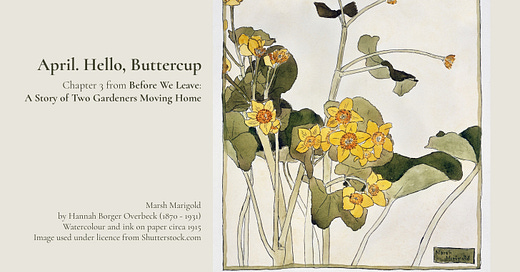

Hedgerows quicken with life. And under the hedgerow halfway up the lonning, where it has flowered every April for all the years we’ve lived here, the marsh marigold, a member of the buttercup family, will be shining in the sunlight.

There are stories which connect marsh marigolds to a Goddess in Norse Mythology. Freyja’s golden tears. When Óðr disappeared, Freyja wept golden tears which turned to gold upon the land. Grief transformed into something beautiful. Golden flowers emerging from dark earth, returning each year. The Prose Edda, a 13th-century collection of Norse mythology written by Icelandic scholar Snorri Sturluson, mentions Freyja’s golden tears, but not their connection to marsh marigolds.

Mythology fascinates me, though. I don’t believe in Norse gods or magic for these stories to feel meaningful. Instead, it’s about recognising something familiar, when you see a pattern you’ve noticed before. Old currents flow beneath the everyday world.

I’ve carried something for years. We were in France. Mum had asked me to empty the teapot in the field behind the tent. I didn’t see the snake until it whipped the ground. Leaning back, as if to strike, it put its tail in its mouth and wheeled away.

“Like a bicycle wheel, and as fast as you like,” I’d said to my grandfather after that holiday, knowing he alone would keep my secret. I must’ve been nearly eight years old because Grandpa died the following year, and the winter after that, my parents separated and put our house on the market.

“Whiplash snakes ... Move by you like a press train,” said Romany Freda Black. That was in 2012. I was on the web listening to Freda describing her experiences of snakes that “moved in cartwheels” to her friend, singer and folk song interpreter, Sam Lee.

I’d first heard Sam perform in London and, later, invited him to play in Cumbria. Freda’s story made my heart hammer, triggering memories of what my maternal grandmother had told me one summer when I’d gone to Sussex to stay with her and her husband Horatio.

Enchanted by their wild garden and Horatio’s collection of preserved insects displayed in miniature vehicles - tiny double-decker buses and motorbikes with sidecars - I told them I’d once seen a snake put its tail in its mouth and wheel away. My grandmother, with her reputation as a fabulist and spieler, looked into my eyes while leaning into the table.

“Only gypsies see cartwheel snakes.”

Years later, after listening repeatedly to Freda Black’s words, I sifted through archives for references to cartwheel snakes.

“The Hoop Snake,” writes a journalist for Gleanings in the Carmarthen Journal, January 1892, “is marvellous enough to have come out of a fairy story, but he lives on the earth ... In this midsummer madness the creature curves itself till the horned tail rests just on the back of its head, and whirls out along country roads or open woodland.”

I didn’t know it then, but snakes that circle like that have turned up in stories for centuries. In Norse mythology, Jörmungandr is the world serpent, coiled around the earth with its tail in its mouth. The Ouroboros. A symbol of return, of something ending and beginning at once. Like our family’s own pattern of departures and returns, like any journey you might trace with your finger on a map, these circular stories speak to something deeper than geography. They suggest that all movement contains within it the seed of return, that even in leaving, we carry the places we’ve been.

Most archaeological funding in this area goes to Roman sites. Hadrian’s Wall and its environs draw the spotlight. But here in our village and beyond, we take pride in the Norse history that runs deep, even if it’s less visible.

David, the village blacksmith, and his partner Sue, with help from a group of like-minded folk, have built two longhouses and a working forge on their land in the village. They use the settlement for school visits, adult learning workshops and gatherings centred on traditional food, craft, and folk music. It’s a way of holding onto what matters, long after the stories have stopped being written.

Sam would enjoy David and Sue’s place. Perhaps he’ll come and stay and sing again, before we leave. I’ve been thinking about Sam and the environmental activism and celebrations he’s involved in - the protection of old songs, the Right to Roam movement, singing with nightingales. His spirit of celebratory resistance.

A few days ago, I read about a man in Yorkshire walking fifty-odd miles dressed as a curlew, raising awareness for World Curlew Day. Part ritual, part art, part protest. The image I saw of him brought to mind an arts group I want to ask Dennis the stick maker about: Welfare State International. I’d been to their lantern festivals in Ulverston, where Dennis lives, back in the day. Their work always had something of activism in it. Processions, fire, water, memory. A belief that beauty, made with care, could anchor a place and its people.

Then today, I learn from a friend that John Fox, the founder of Welfare State International, died last month. The timing feels like those old patterns surfacing again.

April 30. Work has begun on sixteen new houses across the lonning, opposite the gable end of our cottage. Construction cannot begin before the welfare units are in place. A flatbed lorry arrives with a bright orange metal container. It is to be the crew’s mess room. We watch the lorry inch up the lonning, but when it scrapes our neighbour’s hedgerow and clips the bank, the driver has to reverse out, find another way in. On the opposite side of the lonning, the hedgerow and the old stone wall are gone, cleared to make way for the housing development.

A jackdaw with a twig hops down into the chimney of The Retreat, a derelict farm next to the converted methodist chapel opposite our cottage. Mabel the spaniel barks in the chapel driveway. Isabel and Richard were the first people to be married at the methodist chapel on Wednesday, August 8, 1894. Their wedding breakfast was at The Retreat, which Isabel’s father, Mark, farmed with his sons, Mark Junior and James.

Tea in the good cups, no toasts. No dancing. I imagine Mark offering thanks and when he spoke of blessings and the work of marriage, his voice caught just once. They ate with quiet joy, just the steady scrape of cutlery and occasional bursts of laughter from the cousins outside. Richard’s nephew, ten, with his wooden leg, the legacy of an accident two years earlier when he’d fallen into the mechanics of a moving grass roller while playing in a field.

Moving past the chapel, here's The Old Vicarage with its flaking paint exterior visible here and there amid a shroud of foliage. Our friend lives here with his grown children - one whose doctoral studies were cut short by Long Covid, the fatigue syndrome that has reshaped so many lives these past years, and her older sibling who needs full-time care. Our friends' dwelling holds within its walls a contemporary struggle and historical echoes, layers of human endurance stretching back generations

I think of the profound resilience required in different eras. The daily navigation of physical limitation, the determination needed when circumstances derail plans. Elizabeth B. lived in The Old Vicarage for decades, a whitesmith’s daughter who became a coal miner’s widow, quietly accumulating the respectability and modest wealth that represented a real achievement for a working-class woman of her era. Elizabeth’s story illuminates the currents that shaped nineteenth-century rural life in Northern England. The intersection of tradition with industrial changes, the ways rural women navigated economic independence, the accumulation of respectability that represented genuine achievement in small villages.

Past the Old Vicarage, Brookwell sits with the solid assurance that comes from two centuries of watching the village change around it. The sash windows and measured proportions suggest stability, even as the stories within its walls reveal anything but permanence. From at least the 1830s this house sheltered a succession of colliery managers and mining officials, each arriving with ledgers and authority, each eventually moving on for whatever reasons. I think of Ann, a farmer’s daughter, Brookwell’s tenant and then Brookwell’s owner as the Great War reshaped rural England. Ann, a woman shaped by hard grace, who learned that keeping animals alive and crops upright required steel in her spine, mud on her boots.

In Bert’s garden now, just looking, not working, I am face to face with a marsh marigold, resplendent on the side of the beck.

I am in the churchyard. Elizabeth’s parent’s headstone barely readable this year. History lost with each passing season.

Like many rural churches, ours has few regular visitors. Most villagers don’t attend services, and with the curate serving several parishes, Sunday worship alternates between different churches in the benefice. But the building anchors our community in ways that transcend faith. Or, at least, it would seem no one wants to see it sold off and converted into a private residence. M and I were married here, before we became villagers, back when we lived on the southwest coast of England. I first got to know this village when my folks purchased a cottage to be close to my stepdad’s daughters. Later, my folks put their home up for sale and M and I, who’d moved to Cumbria and were renting, bought it. So, in one way, the church witnessed our beginning in this place.

The village’s medieval core around church and green, those ancient tofts and crofts I’ve described before, sits where the springs emerge most reliably. This isn’t coincidence. The clustered settlement pattern (which later became linear) makes sense when viewed through the lens of water availability. There’s an east-west dyke coursing through the village that, in time, created springs and becks. Over geological time, the dyke acted like a dam within the earth itself. Water moving through the limestone’s natural fractures and cavities encountered this impermeable wall, got forced upward, seeking alternative routes to the surface. The path of least resistance but, sometimes, forced to take unexpected turns.

The geology creates perfect conditions for marsh marigolds. They need wet soil, thrive where water seeps and pools. Norse settlers would have understood this immediately. Good springs meant good settlement sites. Where marsh marigolds grew thick, water ran reliable. Of course, over time, farmers drained the land and turned it to cultivation. There must have been meadows of marsh marigolds once, just as there are meadows of meadow buttercup today.

Last year, archaeologists working at High Tarns Farm, ten miles away from the village, unearthed the largest Norse Age building ever found in Britain. The structure, measuring one-hundred and sixty-five feet long and fifty feet wide, dates to between A.D. 990 and 1040. While Norse culture is well-documented in Cumbria through place names and dialect, there’s little surviving evidence of buildings from this period. The blacksmith, David Watson, puts the discovery in perspective. He tells me the larger of his two longhouses would fit inside it four times over.

“Tis a whopper, the largest known Viking structure in Britain,” he says.

But the Norse left more enduring monuments than timber and stone. Our becks and gills. Our thwaites and fells. Linguistic amber preserving Norse heritage long after these first settlers had died. I can easily imagine fields of marsh marigolds, perhaps reminding the first farmers that, even after the longest separation, beauty returns.

(Music outro Waltheof produced by Bee Lilyjones.)

Join as a Free Subscriber and receive:

Occasional podcasts and long-form essays exploring the connections between people and place over the passage of time.

Reflections on the process of researching and making a community archive.

Lay it on the Line, where curiosity meets candour. A collective of women with an inquisitive, open-hearted approach writing about art, ecology, philosophy and place. Once a month throughout the 2025 season. With

, , , , , and .

Join as a Paid Subscriber (£50/year*)

Paid subscribers receive all free content and:

Work-in-progress chapters from Before We Leave: A Memoir of Two Gardeners Moving Home in written and audio formats.

Occasional original ambient soundscapes and field sounds, recorded/composed, and produced by Bee Lilyjones and friends.

One-to-one support for work that helps preserve local knowledge.

One-to-one support for people interested in regenerative gardening and ecological horticulture.

Please message me if paying for a subscription isn't an option for you - I'd be happy to gift you a year's subscription. I want these stories and sounds to reach everyone who might find comfort or inspiration in them.

* Please note that Substack subscriptions through the app may cost £20 more than subscribing on the web due to Apple and Google’s in-app purchase fees.

Share this post